Recent news reports[1] are claiming that the references to camels in the patriarchal narratives (Gen 12:16; etc.) of Genesis are ‚Äúanachronistic,‚ÄĚ or historically out of place, because there is allegedly no evidence for camel domestication before the tenth century BC. This claim is actually not new, since it was made by W. F. Albright over seventy years ago, but is it true?

First of all, a methodological comment is in order. Claims about the Bible‚Äôs (a)historicity based on the absence of evidence are notoriously impossible to substantiate. It is apt to cite here the old adage, oft credited to Egyptologist Kenneth Kitchen, that ‚Äúabsence of evidence is not evidence of absence‚ÄĚ.

Second, we need to clarify that the original journal publication does not exactly make the sweeping claims that are made in the recent news reports. The brief article by Lidar Sapir-Hen and Erez Ben-Yosef in Tel Aviv (‚ÄúThe Introduction of Domestic Camels to the Southern Levant: Evidence from the Aravah Valley,‚ÄĚ vol. 40 [2013] 277-285) looks only at the extant zoological evidence in the southern Levant (Aravah Valley and Negev). That is, their focus is regionally limited; it is not a study of camels in the biblical world broadly which would include Mesopotamia, Egypt and beyond. They also abstain from discussing the significant body of textual evidence for camels from the Bronze Age in the ancient Near East.

Third, the Tel Aviv study only names the dromedary (one-hump camel) and says nothing about the Bactrian (two-hump) camel. While I might agree that the extant faunal evidence for the dromedary in patriarchal times is meager or non-existent, this says nothing about evidence for the Bactrian camel, and it says nothing about textual or iconographic evidence for camels in the ancient Near East. There is actually substantial evidence currently available for the domestication of the Bactrian (two-hump) camel in the middle of the third millennium BC (ca. 2500 BC), which allows a comfortable historical context for the setting of the references in Genesis.

The leading expert these days on camels in the biblical world is Martin Heide. Rumor has it that he is working on a book-length treatment on camels to be published by Eisenbrauns in the same series as my Donkeys book (called History, Archaeology, and Culture of the Levant). Heide‚Äôs recent article on the topic, which is quite extensive (53 pages), presents all the support for the claim I made above (see K. M. Heide, ‚ÄúThe Domestication of the Camel: Biological, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel and Arabia, and Literary Evidence from the Hebrew Bible‚ÄĚ in Ugarit-Forschungen 42 [2010]: 331-384). Here is a snippet from Heide's tentative conclusion:

‚ÄúThe archaeological evidence points to the fact that the Bactrian camel was domesticated before the dromedary and was put into use by the middle of the 3rd millennium or earlier‚Ķ [The Hebrew word for camel] in the patriarchal narratives may refer, at least in some places, to the Bactrian camel‚Ķ The archaeological and inscriptional evidence allows at least the domesticated Bactrian camel to have existed at Abraham‚Äôs time‚Ķ‚ÄĚ (pp. 367-368).

Essentially this means that Kenneth A. Kitchen‚Äôs remark on this perennial issue still holds true. He says: ‚ÄúThe camel was for long a marginal beast in most of the historic ancient Near East (including Egypt), but it was not wholly unknown or anachronistic before or during 2000-1100. And there the matter should, on the tangible evidence, rest‚ÄĚ (On the Reliability of the Old Testament; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003; p. 339; italics his).

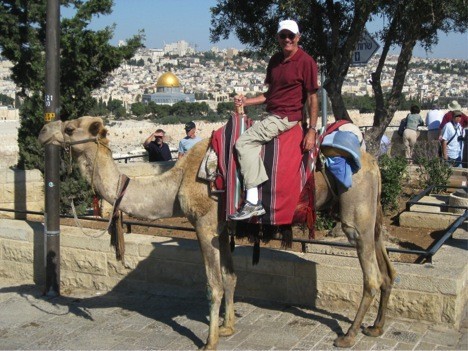

On a lighter note, here is a picture documenting our very own professor, Joseph Hellerman, mounted on a dromedary in Jerusalem. Since Dr. Hellerman is a patriarch of sorts, perhaps this picture could be used as some form of evidence in the recent debates. : )

ļŕ›ģ ”∆Ķ

ļŕ›ģ ”∆Ķ

.jpg)