Questions of social justice have become highly combustible among Christians. Part of the problem stems from the triggering term ‚Äúsocial justice.‚ÄĚ We could use those words to describe what our ancient brothers and sisters did to rescue precious little image-bearers who had been discarded like trash at the literal human dumps outside many Roman cities. The same two words could describe William Wilberforce‚Äôs efforts to topple slavery in the U.K., along with Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman in the U.S. Nowadays, the same word combination could even describe Christian efforts to abolish human trafficking, work with the inner-city poor, build hospitals and orphanages, upend racism and so much more.

But for many brothers and sisters, the term is packed with altogether non-Christian and often anti-Christian meanings. ‚ÄúSocial justice‚ÄĚ has become a banner for organizations with a mission to ‚Äúdisrupt the Western-prescribed nuclear family structure,‚ÄĚ movements seeking to advance the multibillion-dollar abortion industry, movements on college campuses that have resorted to violence to silence opposing voices, and movements that seek through force of law to shut down businesses and groups that will not bow to their orthodoxy.

Much of the current opposition among Christians over ‚Äúsocial justice‚ÄĚ has to do with those opposite reactions the term sparks on either side. For unity‚Äôs sake, it is worthwhile to ask together: What are the kinds of ‚Äúsocial justice‚ÄĚ that we can agree are beyond the bounds of our faith as we seek to fulfill God‚Äôs command (not suggestion) to ‚Äúdo justice‚ÄĚ (Jer. 22:3). I offer seven points where I hope we can all agree.

- We should heed Scriptures to love one another with a love that ‚Äúis not easily offended.‚ÄĚ This means we avoid ideologies that inspire chronic offendedness.

- We should seek the supernatural fruit of the Spirit, which is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Therefore, we shouldn’t welcome ideas that create a spirit of suspicion, hostility, factions, fear, labeling and assuming the worst of others’ motives.

- We should celebrate the fact that ‚Äúthere is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus.‚ÄĚ This means we must reject every ideology that condemns people for their skin tone, gender or social status.

- We should look to the Creator to define us. This means we must resist the mainstream message that human meaning and identity are defined subjectively by the creature, and that anyone who challenges our self-defined selves is an oppressor.

- We should look to family and reconciliation as the Bible’s model for Christian living, not intergroup warfare. Therefore, we should refuse to play the game of identity politics from the left or the right. Jesus destroyed the wall of hostility between Jew and Gentile, uniting people from every tongue, tribe and nation.

- We should embrace male-female differences as God‚Äôs ‚Äúvery good‚ÄĚ idea. Sexual distinctions are not inherently oppressive. We cannot simply erase such distinctions in the name of ‚Äúsocial justice‚ÄĚ without losing something precious and beautiful.

- We should stand boldly for the full humanity of unborn image-bearers of God, loving and protecting those women and their offspring who are exploited or terminated by the abortion industry. We should roundly reject anything calling itself ‚Äújustice‚ÄĚ that celebrates abortion.

The Bible does not merely command us to execute justice, but to ‚Äútruly execute justice.‚ÄĚ (Jer. 7:5). I pray that this meager list of seven points helps our churches do just that with greater unity in our divided age.

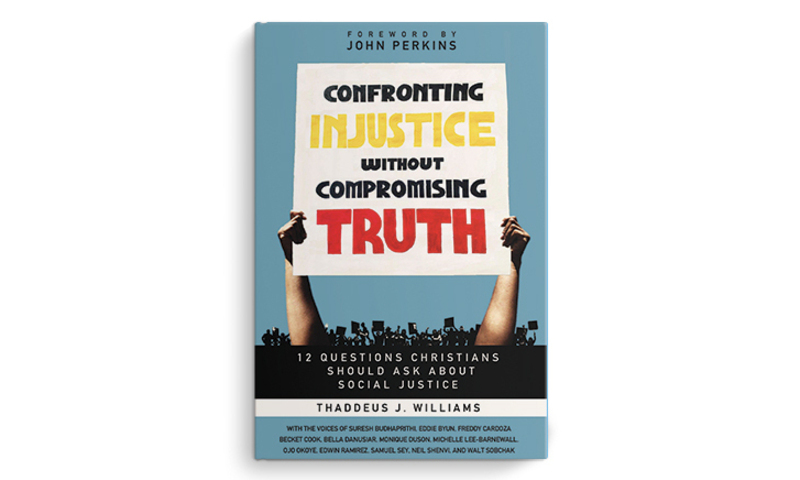

For deeper biblical insights on how the gospel ought to shape our justice pursuits see Thaddeus Williams‚Äô recent book, (Zondervan, 2020) with a foreword by living civil rights legend John M. Perkins. Williams (‚Äė01, M.A. ‚Äė05) serves as associate professor of theology at ļŕ›ģ ”∆Ķ.

ļŕ›ģ ”∆Ķ

ļŕ›ģ ”∆Ķ

.jpg)