Ralph Waldo Emerson famously said, âWhat we are worshiping we are becoming.â In other words, our deities shape our identities. Let us call this Emersonâs Law. Consider this law in the lives of two men:

Charles Darwin said, âMy chief enjoyment and sole employment throughout life has been scientific work.â What effect did elevating scientific work to the place of supreme importance have on the kind of person Darwin became? Says Darwin: âMy mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts. ... I have tried lately to read Shakespeare, and found it so intolerably dull that it nauseated me. ... The loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness.â

An extraordinarily gifted man was turned into a scientific law grinding âmachine,â a man whose love for great poetry turned to nausea, whose heart for art and music slowly turned to stone. Darwin came to see himself, in his words, as âa withered leaf for every subject except Science.â

Consider Emersonâs Law at work in the life of a man who has been branded âAmericaâs first and best homegrown philosopher.â This celebrated philosopher offers the following account of how his object of worship affected his soul over the years: â[It] brought an inexpressible purity, brightness, peacefulness and ravishment to the soul. In other words, it made the soul like a field or garden.â Two gifted men. One became a âwithered leafâ and the other a âgarden.â

This garden of a man was a valedictorian graduate of Yale, where he enrolled as a Latin-, Greek- and Hebrew-fluent 12-year-old. He was instrumental to Americaâs First Great Awakening. He served as president of Princeton University. He was also an adoring husband to his teenage sweetheart and wife of over 30 years, with a full quiver of 11 deeply loved children. One study traced âone U.S. vice president, three U.S. senators, three governors, three mayors, 13 college presidents, 30 judges, 65 professors, 80 public office holders, 100 lawyers and 100 missionariesâ back to his Massachusetts home. That garden of a man was Jonathan Edwards.

Long before Edwardsâ success as a philosopher, theologian, revivalist and family man, he found a worthy object of lifelong worship. At age 19, Edwards wrote, âResolved ... to cast and venture my soul on the Lord Jesus Christ, to trust and confide in him, and consecrate myself wholly to him.â This glimpse into the center of young Edwardsâ solar system is essential to making sense out of the man he later became. ...

This brings us to my central point: Jesus is the most glorious Being who exists, the most massive and radiant Person our lives could possibly orbit around. The good things we enjoy in life are, in Edwardsâ words, âscattered beams, but he is the sun.â He can shape and expand and illuminate and grow us in ways that no amount of money, or power, or lovers, or chemical rushes, or any other conceivable object of worship can. Whether or not we worship him will make a crucial difference in what kind of people we can expect to become, whether we are becoming withered leaves or gardens.

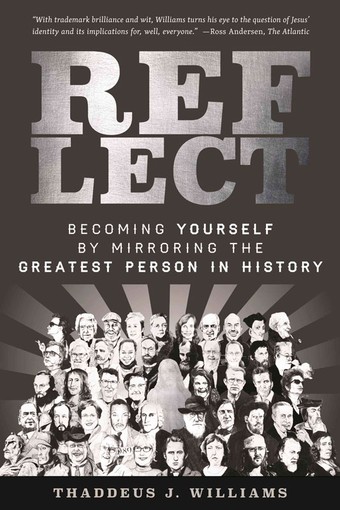

Adapted from , by Thaddeus J. Williams (â01, M.A. â05, assistant professor of systematic theology), Weaver Book Co., January 2017.

șÚĘźÊÓÆ”

șÚĘźÊÓÆ”.jpg)